Don’t Kill That Bug: New Research Shows Insects Do Have Feelings and Emotions Just Like You

BY JUSTIN FAERMAN

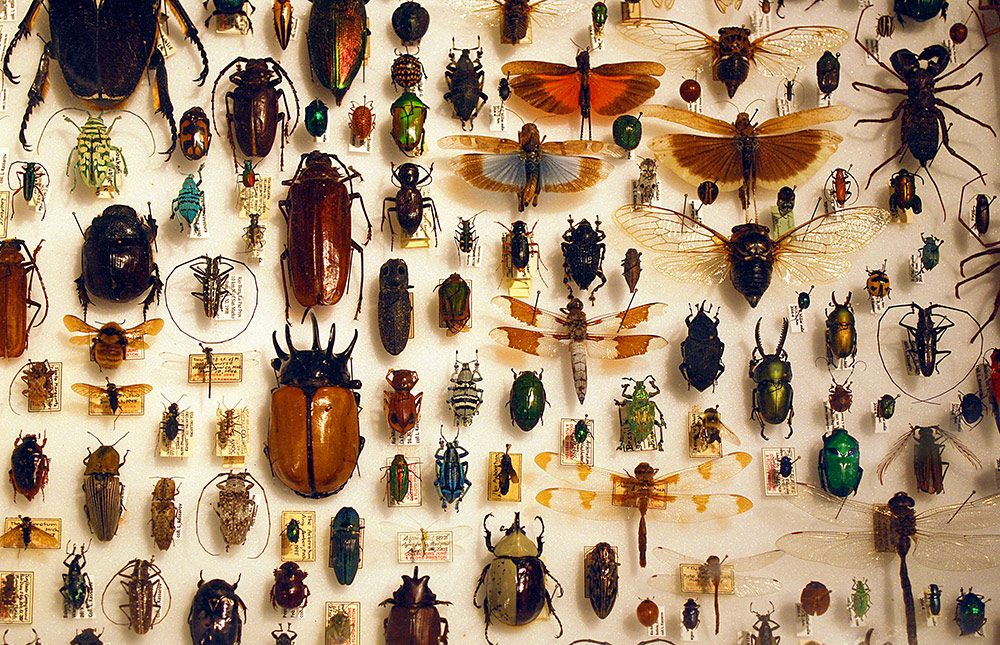

new research is showing that insects do indeed have feelings and emotions and are responding to their environments in complex ways just like us. photo: barta iv

new research is showing that insects do indeed have feelings and emotions and are responding to their environments in complex ways just like us. photo: barta iv

After a millennia-long debate between the kill and catch-and-release camps, it finally seems as if the scale has been tipped in favor of the latter. Multiple studies emerging from various research institutions from around the world have revealed that insects have feelings and emotions—they exhibit very specific behaviors that do in fact show that they have feelings like fear, anger and empathy, perhaps encouraging us all to have a bit more compassion for the multi-legged and winged friends we share the planet with.

One of the many experiments showing that insects do have emotions worth noting shows that insects exhibit different behaviors depending on their perception of their environment, which is a key scientific marker of an emotional, interpretative feeling reaction and one that is in line with how humans and other animals with known emotional capabilities react. This study [1] comes from the Institute of Neuroscience at Newcastle University in England. Essentially, a colony of honeybees was placed in a vortexing machine that vigorously shook them to simulate a badger attack on their hive. As you would imagine, the bees became quite agitated, which allowed researchers to observe differences in their behavior indicative of insect level feeling and emotional state change. What they found in the bees drew close parallels to how human and other feeling-capable animals would react in a similar situation.

When we are upset or agitated, it is not uncommon for us to take displeasure in things like food, sex or social activity that we normally otherwise enjoy. After a bad breakup, you may not feel like eating for days, not even your favorite foods. The researchers observed similar behaviors in the bees. After agitating them in the vortex machine, the bees were then presented with different aromatic solutions containing different proportions of two smelly chemicals: octanone, which the bees had been trained to associate with a preferred sugary treat, and hexanol, which they had been trained to associate with an unpleasant, bitter taste.

What the researchers observed is that the shaken bees had in fact become agitated, and they exhibited behavioral traits indicative of anger and anxiety, demonstrating feeling states existing in insects. The bees actually became more likely to react to the hexanol in the various mixes and avoid them altogether; whereas, in the unagitated state (simulated with a control group of calm bees), their preference was far more tolerant of the hexanol. The researchers labeled this as pessimistic cognitive bias, referring to its negative effects on the bees’ perception and emotional state. Furthermore, the researchers also observed significant changes in the neurotransmitter levels of shaken bees: lower levels of hemolymph dopamine, octopamine and serotonin, all of which are associated with positive mood to varying degrees, indicating that indeed the insects had feelings and emotions.

A somewhat similar experiment [2] was conducted with another species of insect, Drosophila flies, also known as fruit flies. In this study, researchers withheld food from the fruit flies for an extended period of time to ensure they were in a hunger state. Then, after providing them access to food, they simulated an approaching overhead predator—ideally to induce fear, anxiety and other emotions in the insects—by covering them with a shadow, similar to what would happen in a real-world scenario.

What they found was that the fruit flies became quite spooked and entered a high-anxiety/high-fear state, causing them to ignore the readily available food for many minutes (a comparatively long period of time in the life a fruit fly, who typically only live for 30 days), which would indicate that they indeed felt emotions.

Empathic Insects

In another fascinating experiment aimed at measuring emotional reactions in insects, scientists found that agitated woodlice were quickly calmed when paired with non-agitated woodlice, which the researchers suggest shows empathic traits. While it easy to try and explain these behaviors away as simple mimicking, when this phenomenon happens in animals like dogs and cats, we readily accept that it is the influence of the calmer animal; or vice-versa in a scenario where, for example, a cascade of dogs starts barking as the result of one dog’s agitation. In fact, researchers can’t even fully confirm that dogs or cats have emotion, yet ask a pet owner, and they will be quick to tell you they most certainly do—and we certainly read into their expressions, as we are emotional creatures ourselves. The difference with insects and feelings is that we as a species are not as familiarized to their modes of expression, and we typically view them as nuisances or fear-inducing creatures themselves, and therefore we tend to overlook some of the signals they exhibit that indeed show that insects have emotional intelligence.

Beyond that, the great spiritual traditions have been telling us for quite some time “as above, so below,” which researchers and quantum physicists are increasingly finding to be true. From that perspective, insects most definitely have feelings and emotional intelligence—as well as plants, animals and everything in between. Either way, one thing is for sure, insects, with feelings or not, are integral to all life on this planet and deserve our care and respect just like any other sentient being.

About The Author

Justin Faerman is a visionary change-agent, international speaker, serial entrepreneur and consciousness researcher dedicated to evolving global consciousness, bridging science and spirituality and spreading enlightened ideas on both an individual and societal level. He is the co-founder of Conscious Lifestyle Magazine and the Flow Consciousness Institute and a sought after teacher, known for his pioneering work in the area of flow and the mechanics of consciousness. He is largely focused on applied spirituality, which is translating abstract spiritual concepts and ideas into practical, actionable techniques for creating a deeply fulfilling, prosperous life. Connect with him at artofflowcoaching.com

Citations

1. Bateson M, Desire S, Gartside SE, Wright GA. Agitated honeybees exhibit pessimistic cognitive biases. Curr Biol. 2011;21(12):1070-3.

2. Gibson WT, Gonzalez CR, Fernandez C, et al. Behavioral responses to a repetitive visual threat stimulus express a persistent state of defensive arousal in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2015;25(11):1401-15.